Did you know that in the past the Paganella Alpine Plateau was an important industrial location? It might seem incredible, but it is true. When our villages were no more than tiny hamlets lost among the mountains, Andalo and Spormaggiore were at the centre of an industrial initiative of international scope and involving a “Glass Factory”.

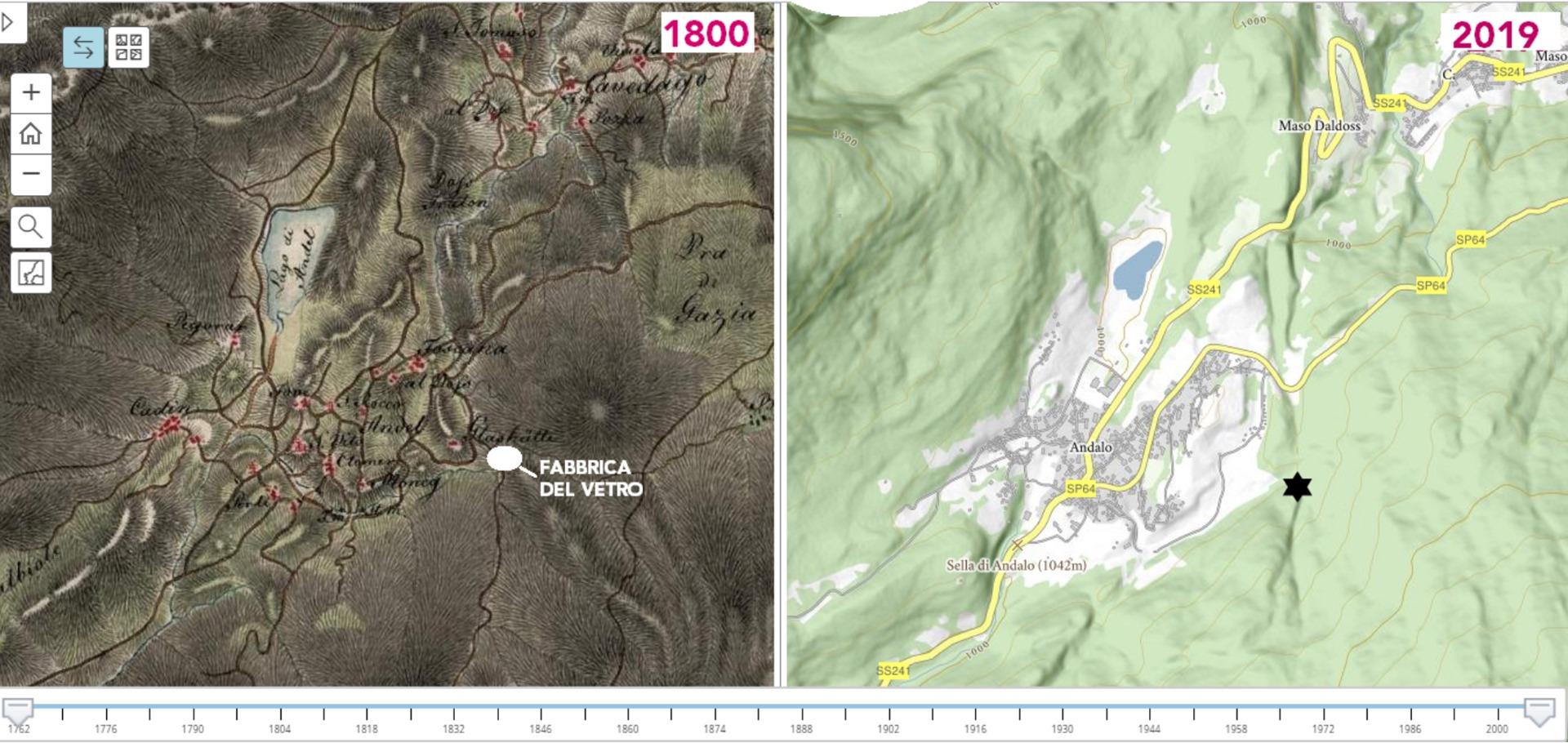

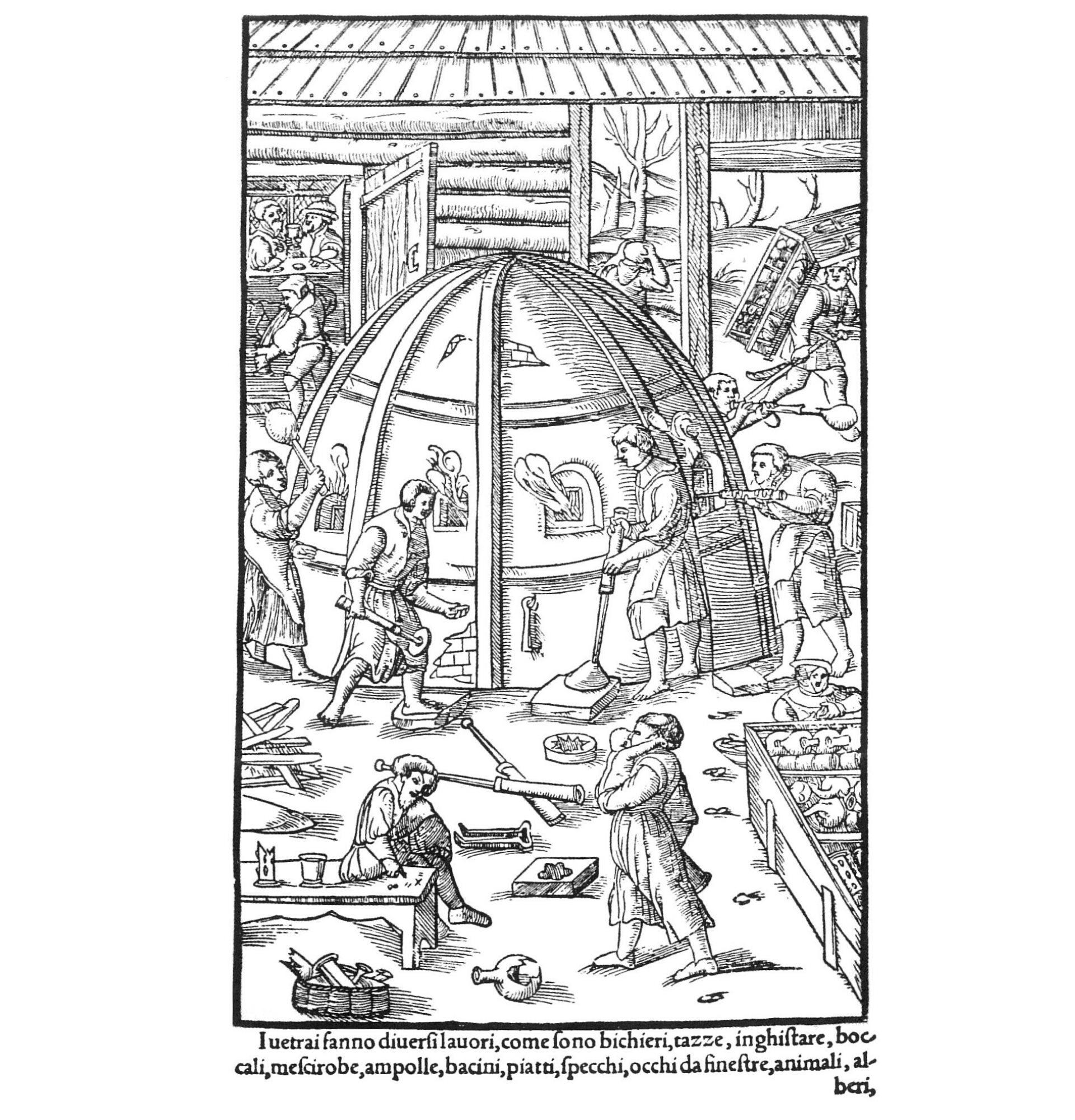

In 1790 a Trentino businessman, Domenico Antonio Vidi, built a factory for Bohemian style glass and crystal production in Andalo at the “Doss de le Mòseghe”, just uphill of Maso Toscana. This entrepreneur had received permission from the Local Council of Zambana to cut wood in the Paganella forests to fuel the necessary furnaces and lime kilns. There was also a stream nearby providing flowing water to drive a grinding mill for the siliceous materials and a saw for cutting timber.

He hired master glassmakers from Bohemia and arranged delivery of the necessary raw materials from across Trentino, Italy, and Europe.

Production started in 1791 and Andalo crystal turned out to be of excellent quality, in no way inferior to the Bohemian production, and it immediately found a strong market in Trento and the bordering Italian territories. This astute businessman managed to survive unharmed through a stormy geopolitical period marked by wars, constantly shifting territorial boundaries, and disputes over trade tariffs.

However, things were not going at all well on the home front. The voracity of the glass furnaces and boilers soon depleted the forest resources of the Paganella. The community passed from concern to dissent, and finally revolt.

In 1819 Vidi was forced to transfer production to a new more modern plant in Spormaggiore, in the area that would assume the name of his enterprise, the “Fabrica” or “Factory”. But here once again he encountered resistance to his activity which, with its 25 door kilns, would have led to the deforestation of the entire Selvapiana woodland area.

Despite great economic success and the appreciation of the Viennese Court, boycotting by the workers in Spormaggiore led to a fall in production and ultimately the closure of the plant in 1828.

This had been an extremely high-technology industry and commercial triumph, but the inhabitants of the plateau experienced only the most negatives aspects of it, which included the destruction of their forest heritage upon which the community depended for survival, and numerous cases of professional diseases of the lungs and eyes among the workers.

The time-honoured balance between man and nature had been broken, with serious risks for the community, in particular for their future. And so, like an infected pustule, the factory was expelled from the Alpine Plateau.